![]()

|

|

History of African American Adoptions

| Before the 1960s, “Negro” adoption referred to the

permanent placement of African-American children or mixed-race children

who had one “Negro” birth parent. Few people considered

transracial adoption a viable option for these children, with important

exceptions such as Pearl S. Buck and Helen Doss, author of The Family

Nobody Wanted. When adoption services were extended to children

of color, they were strictly segregated and matching mattered just

as it did for their white counterparts. But these children were

placed in families so infrequently before 1945 that “Negro”

adoption was considered part of the revolution inaugurating special

needs adoptions after World War II. Adoption resource exchanges

that published monthly listings of waiting children and families

were first used to find homes for “Negro” children.

By the late 1960s, these exchanges were widely used to place all

“hard-to-place” children.

For a good part of the twentieth century, African-American birth parents and children were simply denied adoption services by agencies because of their religion, race, or both. In some states with large African-American populations, such as Florida and Louisiana, not a single African-American child was placed for adoption by an agency for many years running as late as the 1940s. Discriminated against and reluctant to establish racially-exclusive organizations when integration was synonymous with equality, African Americans relied instead on traditions of informal adoption to take care of their own. By midcentury, estimates were that up to 50,000 African-American children were in need of adoption, but would probably never find permanent homes. The U.S. Children's Bureau began including race in its reporting system in 1948 and during the 1950s, a number of innovative programs around the country began recruiting non-white parents. From New York to Chicago and Los Angeles to Washington, DC, child welfare professionals and civil rights activists came together to promote culturally sensitive policies, integrate agency staff, and do community outreach. “You don't have to be a Joe Louis or a Jackie Robinson to adopt children,” declared one encouraging radio spot created by the Citizens' Committee on Negro Adoptions of Lake County, Indiana. The National Urban League Foster Care and Adoptions Project, founded in 1953, and Adopt-A-Child, founded in 1955, took big steps toward promoting “Negro” adoption nationally. Adopt-a-Child lasted for five years, received more than 4000 inquiries from around the United States and the Caribbean, and facilitated the placement of more than 800 children before running out of money. Most “Negro” adoption programs were located in cities with significant African-American and immigrant populations. In San Francisco, MARCH (Minority Adoption Recruitment of Children's Homes) had a large caseload of “Spanish-American,” Chinese, Filipino, Hawaiian, Japanese, Korean, Samoan, and American Indian as well as “Negro” children. Some states with overwhelmingly white populations also initiated projects: The Children's Home Society of Minnesota launched PAMY (Parents to Adopt Minority Youngsters) and the Boys and Girls Aid Society of Oregon sponsored “Operation Brown Baby.” These programs did not promote transracial adoption, but they received numerous inquiries from white couples. After years of hard work had not eradicated the racial bias that made it difficult for African-American families to adopt, a few agencies began to cautiously challenge race-matching by placing African-American children in white homes. Parent-led organizations such as the Open Door Society and the Council on Adoptable Children also emerged during the 1960s to publicize the needs of waiting children. Only tiny numbers of African-American children were ever adopted by white parents, but these transracial adoptions reached their peak around 1970, when perhaps 2,500 such adoptions took place. This trend followed other important developments, especially Native American adoption (through the Indian Adoption Project) and international adoption, in which significant numbers of children from Asian countries crossed lines of race as well as nation to become members of American families. |

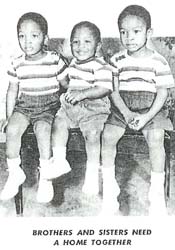

Pictures (above and below) from a brochure to recruit African-American adoptive parents for “heartbreak babies,” City of New York, Department of Welfare, c. 1950

During the early twentieth century, the U.S. Children's Bureau publicized many threats to African-American child welfare. A rural tenant farmer's cabin with daylight showing between the logs was one example.

An infant-care exhibit featuring an African-American doll, early twentieth century

Indianapolis children

in need of social services, 1940s |

Permission to use the above information and

photos were granted by Ellen Herman.

To learn more about The

Adoption History Project, please contact:

Department of History, University of Oregon

E-mail: adoption@uoregon.edu

About the Project and the Author

© Ellen Herman